Are Drones ‘Law Enforcement’s Future’?

The courts ruled a 24/7 drone surveillance pilot program operated by the Baltimore police in 2020 was unconstitutional. But as the technology becomes more ubiquitous in U.S. police agencies, we take another look at a study that analyzed the original Baltimore pilot.

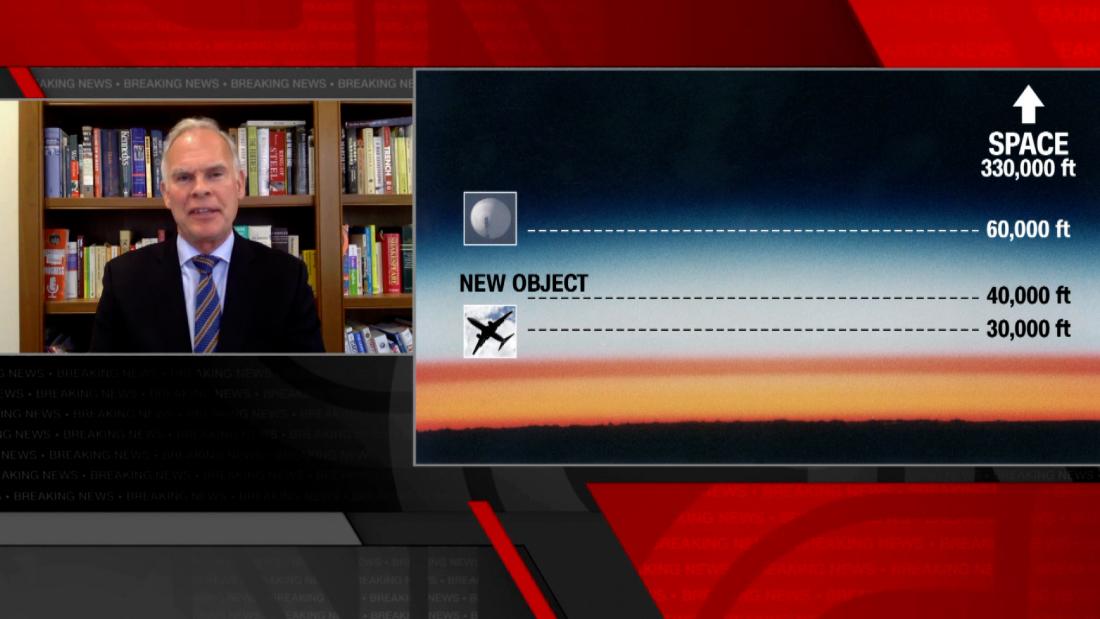

Illustration courtesy Electronic Frontier Foundation

In May 2020, the Baltimore Police Department (BDP) reimplemented an Aerial Investigation Research Program (AIR), four years after the department discontinued a similar program after public opposition.

The program was one of the first to incorporate the 24/7 use of drones in policing, and it was met with swift opposition from critics, who warned it infringed on the privacy rights of Baltimore residents.

The 2020 project continuously captured an estimated 12 hours of coverage of 90 percent of the city each day for a six-month pilot period.

After a long court fight, with support from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, by the Brennan Center for Justice, Electronic Privacy Information Center, FreedomWorks, National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and the Rutherford Institute, in July 2021 Baltimore’s Fourth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled it was a violation of the Fourth Amendment.

In February, Baltimore city councilors voted to end the program.

But as their use has become more common in war theaters, and technology is improving, drones are likely to have a steadily increased profile as a policing tool.

According to the most recent figure provided by the Atlas of Surveillance (a project of EFF and the University of Nevada), at least 1,172 police departments nationwide are using drones for missions ranging from search and rescue to surveillance and crowd monitoring.

“Over time, we can expect more law enforcement agencies to deploy them,” says the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

“Drones don’t disappear once the initial justification for purchasing them no longer seems applicable. Police will invent ways to use their invasive toys–which means that drone deployment finds its way into situations where they are not needed, including everyday policing and the surveillance of First Amendment-protected activities.”

So it’s worthwhile to review the original Baltimore program for clues about how to manage a tool that Police Chief Magazine, a publication of the International Association of Police Chiefs, calls “Law Enforcement’s Future.”

The review and auditing process originally proved promising for a city then ranked as the fourth most dangerous in the country as it tries to balance privacy and public safety.

The Policing Project at NYU Law, which works to partner communities with police, provided an audited report of the refurbished AIR program in Baltimore.

The report, posted online last month, found that the reestablished AIR Program has mostly followed the rules, despite some significant deviations, like threats to privacy and inequitable surveillance.

Also, the report found that the new program works more democratically than the 2016 program.

Still, the report offered recommendations to mitigate the potential of invasive surveillance, such as requiring authorization from a legislative body to limit the control the BDP has on surveillance.

“AIR collects data in bulk about the movements of people in its range, the vast majority of whom have done nothing in particular deserving of the government’s attention,” the study says.

Additionally, while the police can use the AIR system in specific cases, like tracking individuals and vehicles from crime scenes, the BPD has made flurries of “supplemental requests” to expand the AIR system usage in its investigations.

As for the privacy risks, the report offers insight that mainly supports the surveillance program.

“Some substantial portion of the population is subjected to surveillance, in the hope of advancing public safety,” the report says. “Were it not for the concern for public safety, there would be no need for surveillance.”

Similarly, the report pointed to several court decisions that support the usage of the sort of surveillance programs used by the BPD.

But while the courts upheld many cases involving police surveillance, the instances were specific. They did not answer all the questions that the AIR system poses, primarily the questions defectors of the program pose, which they say violate the first and fourth amendments.

In Carpenter v. United States, the Supreme Court decided that the government could not acquire over seven days of site location information from an individual’s cellphone from a cell service provider without a warrant or probable cause to track that individual’s movements.

While the AIR program is different in ways, the report says it can be more powerful than the cell phone information from the Carpenter case and sometimes less powerful. However, it still questions how surveillance can be used lawfully.

Currently, as the BDP stresses, the “vast majority of the imagery…will be deleted,” and “any imagery not identified as relevant to a criminal investigation and reduced to an evidentiary packet will be destroyed after 45 days.”

Still, imagery often remains, according to the report.

But as the study proposes, legislators can play a more active role in cleaving through some of the legal complexities of the surveillance system. The study says the City Council should make most of the decisions.

The report concludes that establishing more specific guidelines on everything from what crimes the surveillance should be on to implementing additional first amendment protections can remedy most of the flaws in the remodeled program.

While the report supports the revamped program, room for closing the racial disparities gap still exists.

In noting the BPD’s difficulty in tackling violent crime, the report says, “it may be in part because in Baltimore—as is the case in other American cities—the relationship between police and the community they serve is so fractured that there is no mutual cooperation and support in suppressing violence and making neighborhoods safe.”

In one case, the 2015 death of a 25-year-old Black man, Freddie Gray, started protests later titled the “Baltimore Uprising,” which partly birthed the original surveillance system from 2016.

According to the report, the FBI, in response to scheduling “large scale demonstrations and protests” after Freddie Gray’s death, deployed surveillance planes—hidden behind shell companies—that were equipped with “sophisticated thermal-imaging and night-vision capabilities.”

The report also noted a 2008 report commissioned by then-Gov. Martin O’Malley concluding that the Maryland State Police had “covertly monitored individuals and groups engaged in anti-death penalty and anti-war activism,” despite lacking “any information indicating that those individuals or groups had committed or planned any criminal misconduct.”

Additional surveillance was used in response to the demonstrations following the death of George Floyd.

“Law enforcement’s use of surveillance technologies, particular ones as powerful as AIR, must be operated transparently and with public input,” the report says. “Adopting a clear, front-end regulatory structure like the one outlined here substantially furthers these goals.”

The authors of the report were: Barry Friedman, New York University School of Law Policing Project; Farhang Heydari; Policing Project, NYU School of Law; Emmanuel Mauleon, Independent; and Max Isaacs, New York University School of Law.

The full report can be found here

Additional Reading: Privacy vs Protection: Does Policing Technology Need Regulation? – The Crime Report

Editor’s Note: In April 2022, a coalition of student groups at NYU organized a “teach-in” to protest the school’s Policing Project. According to one participant, the teach-in was aimed at drawing attention to the organization’s “complicity in causing community harm — specifically through some of the funding streams as being directly funded by police weaponry, police surveillance and police technology.”

James Van Bramer is associate editor of The Crime Report

Landwebs

Landwebs